Otherlanders unite!

Yeah, it's Spring but I'm still hibernating. Unfortunately, I have to go

to work, so that's not possible. But when I get home, I like to curl up

on the couch with a glass of wine and immerse myself in my new

obsession: true crime. Awww, lemme guess, I'm not alone in this? ;) At

the moment, my favourite goosebump-inducers are dangerous cults and

sects. I'll just say Jonestown Massacre. Yeah, I do admit having an

uncomfortable gut feeling and a pinch of shame, but since that's the

fashion right now, I've put together a few hair-raising cults from the

fields of SF, fantasy and horror for you as well. If you're in the mood

for sunshine, just skip this introduction and wait until April. In the

second trilogy of Glenn Cook's "The Black Company",

"The Stranglers" are up to mischief. Incidentally, this cult is loosely

based on the real "Thuggee Cult" from India, which formed in the 19th

century and is said to worship the Hindu goddess Kali. "The Stranglers"

worship "Kina", who is also - how surprising - a goddess of destruction.

China Mieville's "Kraken" is a somewhat

easier read - here an pickled specimen of the titular eight-armed

creature is stolen from a museum. This is a consequence of a veritable

underground war between various occult sects. One of them worships

squids, sees a Danish historian as their apostle, and considers the

stolen specimen to be a God. Okay. In the first chapter of Terry Pratchett's "Guards! Guards!"

the author does what he does best: makes us laugh uncontrollably. He

introduces so many weird cults and sects that you might accidentally

stumble into the wrong top-secret meetings - especially since they all

live next door to each other. In Margaret Atwood's "The Year of the Flood",

the two main characters immerse themselves in a radical environmental

group that has religious tendencies and calls itself "The Gardeners",

although technically no one is brainwashed here, so it's difficult to

define it as a cult. Sometimes the boundaries are blurred, as with the

extremely popular "Parable of the Sower" by Octavia Butler.

It's actually about a young woman who struggles through apocalyptic

America and tries to retain her humanity. She achieves this by founding a

new religion, which is beautiful in itself, but definitely has cult

tendencies.

In Emma Newman's "Planetfall" and "After Atlas", the cult "The Circle" leaves Earth in search of God, and in Robert Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange World",

a man returns to Earth from Mars, takes a close look at all religions

and then founds his own church, in which polyamorous sex is considered a

top priority. The book is quite explicit for its year of publication,

1961, but has not aged particularly well. Few writers have used cults

and sects with as much relish as Lovecraft. He not only

presents us with the cannibalistic de La Poer family cult and the

classic Chthulhu cult (ah, here we go again with the Great Old Ones...),

but there are also witch cults and voodoo groups. It's almost like he's

tampering with everything that makes a good cult, isn't it? "Rosemary's Baby" by Ira Levin is a CULT classic (pun intended), but I'd be spoiling it if I said why. And the superb "Last Days" by Brian Evenson

follows a kidnapped detective deep into the depraved turmoil of a cult

that believes amputations bring you closer to God. Wasn't there a

strange bit in one of the "Eragon" books where a couple of weirdos did the same thing? Finally, I recommend Katherine Dunn's wonderfully dark "Geek Love". Because strange cults can sometimes form within a family.

So, enough gloom for now, spring is here and we need to gather all our

strength for the sunshine and happiness that awaits us the day after

tomorrow. Then there will finally be endless fun and optimistic

introductions again!

Stay strong my friends,

Esther from the Otherland

(not a cult)

Science Fiction

John Wyndham

The Kraken Wakes

Penguin: €12

( Audiobook from libro.fm )I've had maritime vibes on the brain recently. Ray Nayler's much-lauded The Mountain in the Sea reminded me of an old John Wyndham novel, The Kraken Wakes. Wyndham is an old favourite of the sci-fi community, with much-filmed eco-creep masterpieces like The Midwich Cuckoos, The Chrysalids, and The Day of the Triffids.

Like all of Wyndham's books, The Kraken Wakes is the apocalypse

seen through the most stereotypical British lenses you could possibly

get hold of. If you've never read one of his tales, I think the best way

to visualise them is to go watch the black-and-white BBC series Quatermass and the Pit.

In one of his books the protagonist genuinely scours a ruined village

(destroyed by sentient plants) for teabags. Our heroes here are

journalist couple Mike and Phyllis Watson, who happen to record a series

of unexplained marvels that would have Fox Mulder salivating, including

hovering fireballs, fast-action ship sinking, and displaced oceanic

sediment. As story after story gets dismissed by the public, they begin

to see a dark pattern. They watch as humanity does everything it can to

ignore, disbelieve, or deny the problem, until one day it may be simply

too late.

It has an unsettlingly slow pace - we are easily halfway through the

book before anyone openly discusses what is going on - and a subtlety to

the language that really gets under your skin. Wyndham was a master of

litotes, the art of understatement, and there are some gruesome scenes

here described with eerie detachment. Reading this in the twenty-first

century, there are also a host of ecocritical factors that hit home.

Hard. The idea of us humans pretending problems don't exist, for

example, or blaming them on others, or simply reacting (with military

force, naturally) instead of acting. The Kraken Awakes has

picked up all sorts of meaning over the 70 years since it first

surfaced. Its imagery has grown more potent. Rising sea levels,

disappearing communities, decimated wildlife, melting icecaps - it is

like Wyndham had a press release from our future. I really enjoyed this

one. It's slow but powerful, and it's a classic for a reason.

[Tom]

Edward Ashton

Mickey7#1

Mickey7

Rebellion Publishing Ltd.: €15

( Audiobook from libro.fm )“Dying isn’t any fun… But at least it’s a living”

Mickey Barnes has a pretty difficult life. Well… lifes,

actually. As the colony Expendable on a new intergalactic terraforming

project on the ice world Niflheim, it's his job to die and be reborn

doing all of the things others don't want to do. Then he is simply spat

out of a 3D printer and continues as before. But when Mickey7 falls

through a hole in the ice only to unexpectedly survive and make his way

back to the colony, he finds he has already been replaced by Mickey8.

Now the Mickeys have a problem: their force commander thinks that one

Expendable is a monstrosity. Two just might get them killed permanently.

With Bong Joon-Ho’s film version hitting the cinemas this spring, I

thought I would go read Edward Ashton’s 2022 sci-fi comedy action. For

anyone thinking it is a radical change of topic for the much-lauded Parasite director: go watch Host.

Ashton’s novel lends itself well to adaption. It is masterfully

balanced: short, vibrant, funny, and even philosophical when it needs to

be. There are knowing nods to all sorts of classic thought experiments.

Our Mickey is a loveable outsider – an everyman in a team of the best

bodies and minds in the universe. You really want him to win – and the

fact that he could be potentially rebirthed come sundown does not take

away from the tension at all. I tore through it in an afternoon and

enjoyed every chapter of it. Looking forward to seeing it on the big

screen. And if you have to imagine Robert Pattinson in the main role, it

can’t be the worst thing in the world.

[Tom]

“Night City isn’t the be-all and end-all…

Everywhere else is just worse.”

Another bunch of nobodies killing time in the rain. The ex-soldier, the

dancer, the doctor, the gangster, the corporate negotiator, and the

techie. An unimpressive ragtag band of amateurs thrown together to

perform a one-off hair-brained heist – sent to steal some hi-tech

package from a private army. Noboby wants this. Each has been

strongarmed, threatened, or blackmailed into being there; each is

surprised when the job actually comes off. The plan is to go their

separate ways, but fate has other ideas, and unfortunately for them,

their many secrets are going to come back to haunt them. More than one

street gang wants to see them pay up or go down for good.

Polish science fiction writer Rafał Kosik rolls out a bleak little caper

in the vein of traditional grand theft narratives. It is not the most

original kid on the cyberpunk block, but hey, it is wearing all the

right brands and it has the lingo down, so it gets along easy enough.

(Kosik wrote the dialogue for the recent Edgerunners TV series,

so he knows his stuff.) I will say it does what it does well, and it is

good fast-food lit – a fun way to spend a couple of afternoons. If you

are really looking for lean, mean, sci-fi-crime-crossover machines

though, go read The City and the City first. Or The Tainted Cup. Or Finch.

[Tom]

William Gibson

The Neuromancer Trilogy#2

Count Zero

Orion Publishing Co: €15,50

"It was such an easy thing, death. The only sound in the room was

the faint steady burr of his teeth vibrating, supersonic palsy as the

feedback ate into his nervous system."

Bobby Newmark, aka Count Zero, is a small-time kid data-hustler with

aspirations of grandeur. His career plan is almost cut short, though,

when the program he is jacking triggers a defence mechanism that fries

him and makes someone bomb out his shitty tenement block. Now he is on

the streets with a gang of neo-Voodoo priests who think he may have seen

the hand of a god.

Turner is an extractor – a security pro who has just woken up in Mexico

with a reassembled body and a head full of someone else’s memories. His

corpo employers give him a bare minimum of beachside downtime and then

set him the most dangerous mission yet: extracting a genius hybridoma

bio-technician from Mass Biolabs and delivering them to rivals Hosaka.

Disgraced gallery head Marly Krushkhova is just about at her wits’ ends

when she secures a job working for Josef Virek, the richest man on the

planet. The task: to find the artist responsible for a series of obscure

sculptures. Sounds easy. Until other people in the art world start

turning up dead.

I finally got round to reading Gibson’s Neuromancer last year, the first of his monumentally influential Sprawl series. Count Zero

picks up in the same universe, although the story very much stands by

itself. It is catchy – the three strands are equally engaging, and we

jump around between them in a way that keeps you guessing. Like any good

Raymond Chandler mystery, there is your fair share of backstabbing,

untrustworthy smiles, darkened alleyways, and sudden character deaths.

Like any good Gibson, the sci-fi is more poetic than techy, so you need

absolutely (count) zero tech expertise to get into it. For Matrix fans.

[Tom]

Horror

Paul Kane and Marie O'Regan (eds.)

Beyond and Within

Folk Horror Short Stories

Flame Tree Publishing: €24

Folk Horror is an odd old vehicle. As a genre it has an absolute love of

academia, yet it has foolish academics as the ones getting eviscerated.

It is often about the power of nature over humans’ naïve reliance on

modern technology, yet it is also a warning against those groups who

worship the countryside. It has a fascination with local traditions and

history, yet it seems to suggest everyone should stay away and mind

their own business instead of trying to learn more about them. Much like

with good crime fiction, there is also something weirdly comforting in

the expected unhappy endings it serves out – like if you have read

enough M. R. James then you are in on a joke. All my favourite short stories were folk horror before I even knew the term: James, Jackson, Aickman, and recently Hurley,

too. These and others have a curious English-speaking bent, but Kane

and O’Regan’s selection traipses through central America and Asia, to

the very opposite side of the planet, in the name of unsettling tales.

There are some expected ideas here. Adam Nevill, for example, gives us “The Original Occupant”, a slow-building prequel to his excellent novel The Ritual, which manages to get all of the sub-genre’s traditional tropes into one ill-advised trip to northern Sweden. John Connolly’s “The Well”

similarly reads like a love letter to the founding folk horror writers,

starting with a classic antiquarian angle and the ill-fated

archaeological investigations of the (real) Augustus Pitt Rivers. (He

has a curious museum in Oxford, if you are ever there.) This genuinely

could be an M. R. James outing – and it has a great ending! Stephen Volk’s excellent “Blessed Mary”

sees a couple take a Christmas break to an isolated village in Wales,

where the Yule tradition involves a parade with a skeletal horse figure

who has an unhealthy attraction towards them. If only they understood

Welsh. Helen Grant has fun with these repeating tropes in “The Third Curse”,

where a very unlucky family find themselves drawn into the fee-world.

It is all fun and games here, until they have to leave. Then it becomes

something else entirely. Arthur Machen would be proud.

While the UK is undoubtedly the homeland of classic folk horror, the new

collection does a good job displaying its success around the globe. So,

we have H. R. Laurence’s “The Marsh-Widow’s Bargain”,

where we get a tale of disturbing burial rites, otherworldly

corpse-witches, and monstrous water-leopards – and one old woman who

will literally say anything to save her own skin. And Lee Murray’s entry proves that stunning weather and gorgeous scenery can be just as troubling as dreich northern woodlands. In “Summer Bones”,

travelling teens Kate and Laurel share a very intense summer job on a

coastal conservation site. The whole story thoroughly undermines Peter

Jackson’s efforts to promote the New Zealand countryside.

What about highlights, then? What to pick? Tough. A few here are just plain brilliant. Alison Littlewood’s “Good Boy”

might win the top spot for me. The protagonist, Dan, finds a puppy at

the bottom of his garden. It has beautiful black hair – and what a size!

Dan names him Gary. His wife Helen is not impressed: Why does the dog

have red eyes? Why does it always smell of smoke? And where does it keep

getting all of those bones from? Funny and frightening in equal

measure, with a good spoonful of dark comedy to complement the creeping

dread. Jen William’s “Rabbitheart”, on the

other hand, takes the prize for giving me the oddest dreams. It tells of

Mira, who has a horrible life as the only kind soul in her cruel,

heartless family. One day her generosity leads her to help a curious

creature trapped in a rabbit snare. The creature moves in, and Mira’s

family’s life is never the same again. This tale genuinely gives me the

creeps, even just thinking about it now…

[Tom]

Sloane leads a not so fulfilling life with her deadbeat cheater of a

husband when he gifts her for her birthday a weekend away (from him)

with her childhood friend Naomi, who happens to be the exact opposite of

her responsible and tedious self – a wildly impulsive party animal.

Of all the things they could have done during their getaway, they decide

to join an orgy with a group of squatters in an ancient house and end

up being turned into vampires, as you do on such occasions.

The husband is quickly disposed of, but there’s this new problem, that unquenchable thirst…

Naomi is trouble. But she’s the kind of trouble I need.

From what I’ve read from Harrison before, which is everything she ever

wrote and I’d read her shopping lists if she published them, I knew

pretty much exactly what I was in for from the beginning. And I find

comfort in that kind of familiarity. I have said it before and will say

it with every new one of her books; I would love to be friends with her

characters, would like to go drinking and on vacations with them, get in

trouble and fight with them and along them only to, in the end, accept

each other exactly as we are, flaws and all. Her friendship stories warm

my heart and she did it again with So Thirsty, which is the story of every Virgo/ Sagittarius friendship, being completely opposite but somehow completing each other.

I’m going through a kind of slump right now and my brain feels like it

can’t handle stuff I usually read, and Harrison’s part chick lit part

horror trope novels always are a welcome stroll out of my comfort zone,

quick to read. Will be eagerly waiting for her next.

[Inci]

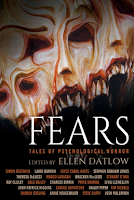

Ellen Datlow <ed>

Fears: Tales of Psychological Horror

Tachyon Publications: €25,50

The name list of contributing authors is impressive. The editor iconic.

The theme subtle, complex, exciting. The 21 short stories are reprints,

means they have been approved already. So, Fears: Tales of Psychological Horror must be a sure-fire winner, right?

The horrors in this anthology are built upon human evil, derangement,

trauma, and in order to get there, the stories make use of atmospheric

narration, hold in suspense, and sometimes, unfortunately, turn to

pathos and sentimentalism. As is the essence of anthologies, Fears

too has its ups and downs, but covers a wide range from creepy

grandfathers with outrageous secrets, toxic friendships, dysfunctional

marriages, serial killers, encounters with murderers, to sharks.

To answer my initial question, the answer is unfortunately no. Despite

its advantages, this anthology does never quite make it. There was maybe

one short story, Priya Sharma's “My Mother's Ghosts” that impressed me, but the others didn't really do it, I'm very sorry to say.

It happens. I'm happy about every Datlow anthology and I'm already anticipating her next.

[Inci]

Kristopher Triana

Riverman#2

Along the River of Flesh

€22,50

As a big fan of the phenomenal Gone to See the River Man, I was

very positively surprised to see that there's a sequel, even though the

first story, the way it unveiled and ended in soul shaking dismay, was

perfect already. I am delighted to say that the second tome of

unadulterated human depravity and extreme horror keeps up with the first

book of what apparently/hopefully will become a longer series.

While River Man focuses solely on serial killer groupie Lori

and the quest she needs to accomplish to get to her idol, brutal

murderer Edmund Cox, the plot of River of Flesh is parted into

numerous characters and points of views; police officer and textbook

incel Keith Drakeson; privat eye Garry Chatmon who was hired by one of

Cox' victim's family; June, yet another teenage fangirl of Cox; and

finally, the beast himself – fugitive Edmund Cox on his way to River

Man, to claim what he thinks he earned for the sacrifices he made for

the mythic creature.

It was as if they'd entered another dimension, a hellscape of coral rock and broken trees where a claret river flowed like the blood of dead gods. What wasn't red was black – the encompassing gorge, the shadows of the thicket, the returning thunderclouds. The redness made grim adumbrations of the world they'd left behind, like the faint image of distant mountains on a smoky horizon. It contorted the features of the known universe into grotesque aberrations, as if the world had shattered and been glued back together, a model forged by a violent hand.

The stone cracked like thunder, every snapping slate having a different tone. They became musical but distorted, each new crack in the limestone producing another strum like the plucked strings of an electric guitar. The sound was sloppy and garbled, a bluesy dirge muddied by a heavy tone, like a guitar's output through a blown amplifier. A crazed, acoustic slide guitar underlined this black requiem, followed by a hushed percussion like chains being dragged across concrete.

Amazing atmospheric passages like the above describing the hellish

parallel dimension the River Man inhabits will chill your spine, and so

will Edmund Cox, who wanders around with body parts of his “darlings” in

his pocket - I realized while reading this that I actually prefer the

River Man to Cox, he scares me much less in that at least he has some

kind of moral compass. I was happy to find something akin to black humor

in this gloomy setting when we reach the end, and Kris once again

surprises with a twisted revelation. And the best part? It looks like

this series just might keep on going and going. The hope is there.

[Inci]

Ji-won’s life falls apart: her father left her family for another woman,

her mother is a mess, her sister hurt and all this affects her grades

negatively.

It even gets worse when her mom starts a relationship with the utterly

unlikable, annoying and invasive George, who starts staying with them

when there's some construction issue in his apartment. Ji-won is having

paranoid thoughts, visions and an irresistable wish to eat George's

bright blue eyeballs. She develops an obsessive appetite for blue eyes

in general, soon succumbs to it and starts acting on it.

I'm very disappointed by this, to say the least... I should have known

by now that every time a book is tagged as "Adult horror" on Goodreads,

if there is a need to specify that, it turns out to be Young Adult, and

although I totally sympathize and can understand the main character's

struggles, my expectations were different. I was in for something much

more gory, ugly, something to scare and repulse me. What I got was the

struggles and worries of a young girl growing up, which is valid, but

not mine. The bad ending gave it the final stroke.

[Inci]

Nonfiction

“Those who dislike fantasy are very often equally bored or repelled

by science. They don’t like either hobbits or quasars… They don’t want

complexities.”

The Language of the Night is a collection of 24 of Ursula K. Le

Guin’s essays. Originally collected in 1979 and then revisited by Le

Guin a decade later, this 2024 reissue has a new introduction by Ken Liu

and a funky new nightclub cover. I shouldn’t need to tell you why you

need another Ursula K. Le Guin book, but essentially you get a series of

introductory essays to her most famous works such as The Dispossessed (which celebrated its 50th birthday last year) and A Wizard of Earthsea, plus some of her more famous non-fiction outings such as “Why are Americans Afraid of Dragons?” (1974) and “Is Gender Necessary? Redux” (1988).

This is a treasure trove of intellectual thought. Thoughts on censorship

and world-building. On character construction and writing as a

profession. On The Word for World is Forest and its relation to the Vietnam war, or Left Hand of Darkness

and gender roles. Her thoughts on Tiptree and Tolkien, Dick and

Zamyatin are particularly stimulating. All in all, it is a fascinating

deep dive into Le Guin’s witty and wise back catalogue, and particularly

her wider thoughts on science fiction and fantasy. Reading through, I

felt like I needed to highlight every third sentence. Even young Le Guin

is already a world-wise sage. I won’t say you are in safe hands here,

but certainly inspiring ones.

[Tom]

Carmen Maria Machado & J. Robert Lennon (Ed.)

Critical Hits

Profile Books: €21

The video game industry has been winning for a while now. In 2024

economics pundits estimated that global sales reached 455 billion US

dollars – that’s bigger than film (by about 8 times), music, and

professional sports.

Far from competing with books, for many readers, games were our way into

English language fantasy, science fiction, or horror – or just the

English language in general. I fondly remember playing Interplay and

Sierra’s clunky LOTR games alongside reading Tolkien’s books.

For all this success though, games and gamers are still widely

ostracised. They are the realm of the asocial, the psychopathic, and the

dweeb.

In Critical Hits, Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon set

out to highlight the cultural importance of video games and how they

have woven their way into every aspect of our lives. In this sharp and

stimulating collection, writers and poets spill the beans on how games

have affected their lives: Halo and Hollow Knight, Fallout 76 and Final Fantasy VI, Disco Elysium and Dragon Age: Inquisition.

It is a really smart and occasionally emotional assault on the senses.

Highlights for me included Elisa Washuta’s “I Struggled a Long Time with

Surviving”, where she discusses The Last of Us and its eerie

parallels to her own experiences with long-term medical issues. Or Ander

Monson’s “The Cocoon”, which investigates the many respawns of Alien

and/or Predator and the notion of memory, asking how we actually

preserve our cultural artefacts. Vanessa Villareal’s excellent “In the

Shadow of the Wolf” examines Norse mythology and trending notions of

white supremacy in games such as Assassin’s Creed Valhalla,

pointing out troubling uses of the Nordic apocalypse. And in “Cathartic

Warfare” Jamil Jan Kochai explores the old saw of video games training

desensitized teen-soldiers and his own experiences as a young

Afghan-American of killing himself (or someone who looks unnervingly

like him) while playing Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.

Gender identity, personal loss, queer relationships, rites of passage,

acts of slavery, pedagogy, the Other, addiction, monstrosity,

hauntology, racism, and love – these essays show how video games have

become one of the most important cultural mirrors of our lives. Time to

start talking about them.

[Tom]

Edward Parnell

Ghostland

HarperCollins Publishers: €19,50

Still in school, his mind full of weird literature and rare birds,

Edward was told one day that his mother was going to die. One word, six

little letters: Cancer. Over the next years, young Ed dove into ghost

stories, other worlds, and the mysteries of nature to escape the tragedy

unfolding around him as his loving family of four was whittled down to

just one.

Now an adult, writer Edward Parnell sets out across the British

countryside to explore the landscapes that inspired the golden age of

folk horror, through writers like William Hope Hodgson, Robert Aickman,

Susan Cooper, M. R. James, Arthur Conan Doyle, Elizabeth Jane Howard, E.

F. Benson and Algernon Blackwood. Along the way he traverses the

marshes, woodlands, clifftops and heaths that link him to childhood

memories of his early life and his family, and he ponders the true

meaning of the word “haunt”.

Ghostland is a unique piece of personal history, combining

nature writing, travel journal, and literary biography. Parnell wields a

deep-rooted love of horror literature and film, and lays this out

alongside actual adventures to the locations that housed the tales. Like

Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers or Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk, Ghostland

is an attempt to cope with grief and loss using all tools available –

however strange they might be. The book looks gorgeous, with a host of

photographs of the locations and woodcut-style illustrations from

Richard Wells. For anyone who enjoys Parnell’s extensive literary

knowledge, go check out his blog (great) and his recent edited

collection for the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series, Eerie East Anglia: Fearful Tales of Field and Fen, which came out Halloween 2024.

[Tom]

Saleem H. Ali

Very Short Introduction

Sustainability

Oxford University Press: €14

The latest in the Oxford “Very Short Introduction” series, Saleem H. Ali's take on Sustainability

dives into one of the twenty-first century's most pressing themes. If

there was a better time to read this book, it was yesterday. Ali’s study

looks into the historical development of sustainability, from the

sixteenth-century German sense of Nachhaltigkeit and the

economical concept of the Commons, to modern politics and alternative

ways of living. His argument dives into topics like energy flows, human

intervention, tipping points, and the function of renewability within

our economies - and along the way he gives nods to familiar faces such

as Kim Stanley Robinson, Greta Thunberg, and Ray Kurzweil. From

techno-optimists to AI modelling, the COVID pandemic to Blade Runner,

sustainability is not a theme merely for woke tree-huggers and

middle-class politicians – it touches everything in our modern

existence, and in the next generation’s. And all that in 130 A6 pages.

Concise, understandable, and well worth reading.

RPG

Dragonbane RPG

Path of Glory

free league: €36,99

“Not so used to the wilderness, are ya? Well, that’s your problem.

Now gimme your money and valuables. Chop chop! Weapons on the ground! No

funny business! Thanks a bunch!”

Path of Glory is a new edition of a Dragonbane campaign that started some four decades ago back in 1985. The new book contains three adventures: The Dead Forest, The Gates of Power, and Heart of Darkness.

A few spoiler warnings straight out of the gates: Path of Glory

is very much a game masters’ book and doesn't really have any extra

content for regular players. It uses the same monsters that can be found

in the core rulebook and the bestiary, and even a lot of the artwork is

reused from these other volumes. (David Brasgalla takes point again,

while Johan Egerkrans provides the cover art.) Moreover, it's tricky.

The campaign is recommended for groups of characters that have already

had 10 to 15 sessions, and who each have a number of heroic abilities on

tap. So it wouldn't really work as a first introduction to Dragonbane either.

With all of that out of the way: it is definitely worth a look in. There

is a lot here to get your teeth into. Much like the campaign in the

core rulebook, Path of Glory is designed to be nonlinear - an

immersive open world full of problems which players can approach as they

like. As well as fighting, characters will have to employ all of their

detective-work, diplomacy, and downright sneakery in order to get

through the dead forest, the underdark, and the lands beyond. Along

their way they will have to deal with the minotaurs Grim and Grum, a

classic black knight which looks like it has fallen out of a Middle

English romance, and hosts of trolls, goblins, and otherworldly

bastards. Classic Lord of the Rings vibes all the way: from

Mirkwood to Moria and back. With the only difference being that you get

to have the dragons on your side here. I won't go into too much detail

but there is even a great Mount-Doom-style finale with troubling

survival odds. Plus Dragonbane always has the one thing that Tolkien doesn’t: murderous ducks.

[Tom]

No comments:

Post a Comment